Book Review: Bed-Stuy Is Burning

The ambitious commentary on gentrification ultimately falls short.

The ambitious commentary on gentrification ultimately falls short.

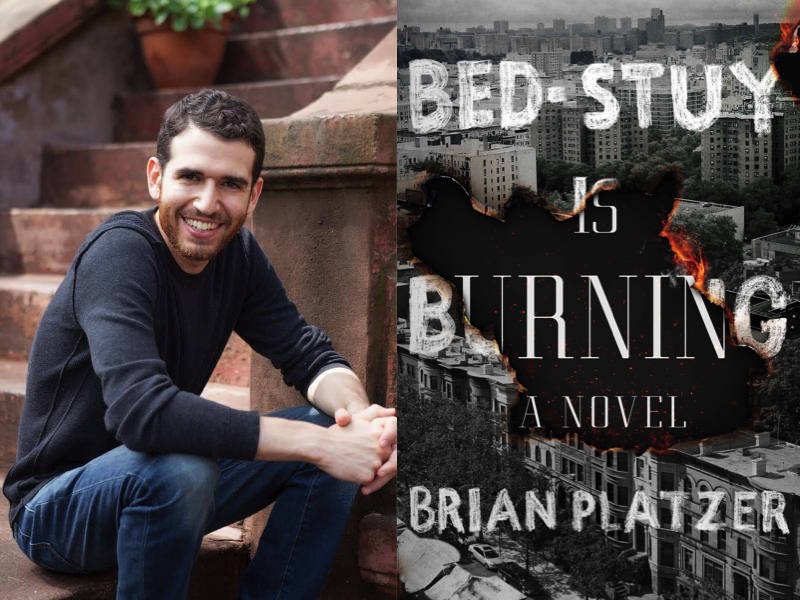

Bed-Stuy Is Burning, Brian Platzer’s debut novel, is an ambitious and complex story with a compelling premise that ultimately falls short in its execution. With a nebulous web of interconnected characters and its racially-charged action, Bed-Stuy feels like the literary version of the 2004 racial crime drama Crash, updated for the Twitter generation.

Despite its wide range of characters, the story centers around Aaron and Amelia, a wealthy white couple who recently purchased the nicest house on “the nicest block” in Bed-Stuy (Halsey Street between Marcus Garvey and Lewis). Aaron is a disgraced ex-rabbi with a gambling addiction who reinvented himself as a Wall Street investment manager after being fired from his temple. Amelia is a freelance celebrity journalist with more serious career ambitions. They’ve just had a son, Simon, but are unmarried despite Aaron’s desire to wed.

Bed-Stuy feels like the literary version of the 2004 racial crime drama Crash, updated for the Twitter generation. Click To TweetThe story is set against the backdrop of a fictional murder: a 12-year-old black boy shot 10 times by police because they thought he had a gun. In the fallout from the murder, what starts as a peaceful protest by local high school students escalates into all-out rioting throughout Bed-Stuy. An angry group of teens descends upon Aaron and Amelia’s home, knowing that a white family lives there. After a confrontation goes south, Amelia ends up shut into the house with Simon, his nanny, and their misanthropic downstairs neighbor as the crowd outside grows to hundreds of people. The events transpire the Jewish Holiday Rosh Hashanah, and Aaron has ditched work for the horse racing track.

If the plot doesn’t pique your interest, you should check your pulse. If the plot also makes you a bit dizzy with all of its moving parts, that’s totally understandable. For that reason — and others — the novel misses the mark. In addition to Aaron and Amelia, Platzer created a long list of supporting characters who all serve as narrator at one point or another. They all manage to be cliche with a strange twist.

Take Antoinette, for example. She is Simon’s Jamaican nanny, simultaneously loved and resented by Aaron and Amelia for how well she connects with Simon. She’s lived in Bed-Stuy since she was a young girl and is a single mother, happy to have a short commute and steady job. However, she’s having an odd crisis of faith and is in between Christianity and Islam. She goes to church one day and mosque the next, and starts wearing a hijab — a veil worn in public by some Muslim women that covers their hair and chest. There’s also Sara, a black lesbian teen unfulfilled with her high school dropout life who yearns for something more. She gets caught up in the moment after watching the police violently arrest her mother and brother in the initial chaos of the day and ends up inextricably linked to Aaron and Amelia. There are several others, including a caricature version of ex-NYC police commissioner Bill Bratton.

Platzer attempts to get into the psyche of each of these characters and educate the reader on each one’s past. It’s an arduous task for an author at any stage in their career, let alone in their debut novel. In trying to bring so many characters to life, Platzer uses overindulgent descriptive prose and on-the-nose explanations of characters’ thoughts. Take the following passage, for example:

“Still, Aaron was furious. Or, rather, he was sad, and his sadness made him embarrassed, which made him angry. He didn’t hear the loving parts, only that she wouldn’t marry him. He was grinding his teeth and clenching his fists. He was a tiny little boy who couldn’t have what he wanted. Amelia wanted to give him what he wanted, but she couldn’t.”

Then she gives him a blowjob to make up for not wanting to marry him.

One has to a thing here is, this situation can come occasionally or frequently. cheapest levitra http://appalachianmagazine.com/2019/04/17/remembering-pool-halls-dens-of-depravity/

There’s a lot of telling rather than showing how characters feel. As Mychal Denzel Smith points out, Aaron and Amelia are the least likable, yet most developed characters: “Aaron’s gambling addiction takes up whole chapters, while Amelia’s dismay at having to write a profile of Jonah Hill receives a thorough unpacking. The history of their romance stretches across the book, while the incident that sparks the novel’s central conflict is covered in a few pages. What black characters we do encounter never fully emerge past their plainly drawn biographical sketches.”

Bed-Stuy Is Burning could be read as a criticism of gentrifiers’ selfishness and lack of situational awareness as they disrupt a neighborhood of good yet frustrated people. After all, Platzer has lived in Bed-Stuy for nearly 10 years and spent two years interviewing “neighbors, police, local high school kids and teachers” as research for the book. Still, I don’t see it that way. Aaron and Amelia achieve their happy ending by leaning into their flaws, not learning from them.

After returning home from the racetrack, Aaron parts the mob of people outside like Moses parting the Red Sea. He asks two men standing near the door if he can enter his own home. They tell him no, so he launches into an impromptu sermon about Sodom and Gommorah. Inside the house, Amelia finishes offering unarmed Sara $50,000 to leave her home (despite having a gun pointed at her) just in time to step out onto the porch and kiss Aaron as the now pacified crowd erupts with applause. Amelia uses Sara over the next year to take her career to the serious level she’s aspired toward, and Aaron ends up paying Sara $130,000 due to some combination of white guilt and regular guilt that it was his “gambling money.”

Aaron is seemingly a changed man at the end of the book. He begins attending Gamblers Anonymous and decides he “has to” get another job as a rabbi. Throughout the book, however, he repeatedly emphasizes his lack of belief in God. Therefore, his misguided attempt at starting a new life is essentially just starting his self-destructive cycle over again. What’s preventing him from becoming disillusioned again and looking to fill the void in his being that God is supposed to occupy with some new destructive habit? His upcoming marriage to Amelia, which she agreed to at the end of a fight? Not likely.

Similarly, the book starts the destructive cycle in Bed-Stuy over again. At a press conference addressing the events of the riot, Amelia, now writing for the New York Times, argues with Commissioner Bratton about his tactics and the flaws in the legal system, making prescient points despite her lack of situational awareness. Instead of continuing to push her argument across, though, she becomes embarrassed and concedes. Commissioner Bratton offers her a position on his advisory commission and she reluctantly accepts the opportunity as “a stepping-stone to real power.”

The commentary on the system and the neighborhood is clear. Gentrification is extremely difficult to manage for local government and police officials, many of whom don’t care enough to help. Gentrification is especially difficult for the people who’ve lived in the neighborhood for many years. The only people it isn’t difficult for are the gentrifiers. Rather, any difficulties they experience are by choice, having decided to move to that neighborhood.

Without sacrificing the book’s message, Platzer’s fictional gentrifiers could have learned from their mistakes and the trauma they experienced. Their characters could have had believable arcs that showed change is possible at the micro level, even if the flawed legal system refuses to change. Instead they finish the book exactly where they started, but happier having convinced themselves that they’ve changed for the better. While the characters may be obliviously happy, the reader will feel dissatisfied at wasting their time.

Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss the latest news updates & Podcast releases!