The Evolution of Brooklyn Through The Lens Of The Borough’s Greatest Rappers

Hip-hop has been the borough's life blood since its genesis 40 years ago.

Hip-hop has been the borough's life blood since its genesis 40 years ago.

Since the beginnings of hip-hop in the parks of the Bronx in the 1970s, New York has been one of the premiere cities for the musical genre. Each borough has its share of influential MCs, its own unique style, and plenty of claims to fame, but Brooklyn is a cut above the rest.

Although Brooklyn’s music has changed greatly over the past few decades, many of the central themes remain the same, and this is as much a reflection of the social and political environment of the borough as it is of the people within it. From the impoverished times of the early 80s, through the crack epidemic and the war on drugs into the 90s, and finally into the tumultuous times of the 2000s and 2010s, many Brooklyn residents have remained oppressed and frustrated. Such extended exposure to a tough environment has bred extreme resilience and an unbreakable spirit among the people in the borough.

Through it all, hip-hop has been there as a means for expressing frustration, celebrating, and coming together for a reprieve from the harshness of reality, even if just for a few minutes.

In its nascent stage, rap consisted of MCs rapping rhythmically over simple drum patterns from the beat breaks of popular music. It began in the Bronx, where rappers would perform in parks and at block parties with live DJs. This quickly spread to Brooklyn as artists began recording in the 80s. Early Brooklyn hip-hop featured two central themes: Brooklyn pride and the hardships experienced in daily life. Two of Brooklyn hip-hop’s earliest artists brought these themes into the spotlight with their music.

Cutmaster D.C. oozes Brooklyn pride from every pore in the original Brooklyn anthem, “Brooklyn’s In The House.” He raps proudly over a simple drum beat about the toughness and work ethic people have in Brooklyn, and makes his case for it being the best borough in New York.

“Well you can tell it’s Brooklyn by the way we rock/24-7, around the clock/We never sleep or get slept on/Kickin’ it live til the break of dawn.”

This came a few years after his 1983 song, “That’s Life,” which provided a much harsher look at the struggles of people on the streets of Brooklyn.

In 1984, rap group Divine Sounds released, “What People Do for Money.” Featuring simple lyrics, the song takes a serious look at (as the title suggests) the lengths people will go to for money. From the very beginning, Brooklyn hip-hop became a creative outlet for people while also providing a platform to spread a message and commiserate with people going through the same struggles on a daily basis.

Around this time, Brooklyn had developed its reputation for being tough, the home of the “stickup kid.” Brownsville native and eventual rapper Thirstin Howl III, an original member of the Lo Life boost crew summarizes life in Brooklyn in the 80s in the short film, Bury Me With The Lo On. “It was wild, especially for the areas of Brooklyn where Lo Lives came from. Killings, shootings, robberies, you know, the crime rate was out of control. Robbing was a way to survive.” As crack and cocaine usage spread rapidly throughout the borough, the murder rate spiked and residents’ quality of life declined severely.

Dwayne Faison of Cypress Hills told the NY Daily News that he and his wife would sleep with their kids on the floor to avoid being hit by stray bullets while they slept. He added, “There was a time when [people living in] several buildings here weren’t even able to come outside and sit on a bench because of the crime that was taking place.” Even Bushwick, now considered hipsterville, was ravaged by the crack epidemic. A 1989 New York Times article describes a block in Bushwick as “an impoverished neighborhood of storefronts is little less than an open market for crack and cocaine. At noon on a recent weekday, dealers pressed packets and vials of drugs into the paying hands of street customers with almost as much regularity as a midtown food vendor selling hot dogs at lunchtime.”

In response to these hardships, Brooklyn residents were forced to toughen up. It was necessary for survival as the murder rate skyrocketed to 1,896 people killed in New York City in 1986. Brooklyn hip-hop took that toughness and made it sound clever over hard-hitting boom-bap drum beats. No one did this better than Big Daddy Kane, arguably one of the greatest lyrical technicians of all time. His song, “Raw,” features clever rhymes that describe him as unstoppable and peerless.

“Attempt to debate so I can humiliate/We can go rhyme for rhyme, word for word, verse for verse/Get you a nurse, too late, get you a hearse/To take you to your burial ground/Because the Big Daddy Kane always throws down.”

Other rappers from the borough overcompensated in their music, flexing confidently before attaining any success. Special Ed’s first album dropped the day before he turned 16, so the odds of him already making “a million dollars every record I cut” — as he claims on “I Got It Made — were slim to none, but that didn’t stop him. Similarly, Chubb Rock raps about hitting on Janet Jackson and rubbing elbows with Frank Sinatra at the Grammys on “DJ Innovator” off of his first album.

The overconfidence in these lyrics is a reaction to growing up in such a violent environment, a tough and confident demeanor can help protect you. But, the lyrics can also be seen as fantastical diversions to keep the artists’ (and the audience’s) minds off of the horrible things going on around them. Either way, the confidence of MCs like these two set the bar for future generations of Brooklyn rappers’ grandiose, confident lyrics as Brooklyn hip-hop began to form its identity.

Another Brooklyn rapper with extreme confidence, MC Lyte was the first woman to record a full-length hip-hop album. In a male-dominated genre, it’s fitting that a Brooklyn rapper would have the gumption and character to blaze a trail for her gender. She didn’t do it timidly, either. MC Lyte wasn’t shy about comparing herself to male rappers or attempting to change the dynamics of male-female relations. Her song, “Paper Thin” preaches female self-respect and taking back control from men, while in “Lyte As A Rock,” MC Lyte makes her case as the best MC, regardless of gender. Her early work paved the way for future strong female rappers not just in Brooklyn, but everywhere in hip-hop.

As the 80s wound down, Brooklyn hip-hop had become a dominant force. With a highly-concentrated population of impoverished and struggling people in the throes of the crack epidemic, hip-hop strengthened the sense of community around a common struggle and frequently allowed for a diversion from the harshness of reality.

With the crack epidemic coming to a close in the 90s, Brooklyn attempted to recover in the aftermath. After the murder rate peaked at 2,245 killings in 1990, it began to decline. Neighborhoods like Brooklyn Heights, Fort Greene, and Clinton Hill came back to life. It wasn’t all candy and sunshine, though. As Jay-Z states in a New York Times op-ed, Ronald Reagan’s continuation of Richard Nixon’s War on Drugs vilified drug dealers and users as the sole cause of economic and social problems. These people, in many cases just doing what they could to survive, instantly became the object of extreme nationwide scrutiny. Brooklyn was no exception.

“The NYPD raided our Brooklyn neighborhoods while Manhattan bankers openly used coke with impunity,” Jay-Z explains in the op-ed. Effectively, the War on Drugs was just a big public relations campaign that scapegoated blacks and Hispanics and led to discriminatory practices from local law enforcement and government. In his conclusion, Jay-Z informs the audience that 45 years after President Nixon initially began the War on Drugs, drug usage rates are more or less the same.

Understandably, racial tensions in Brooklyn were high in the 90s. Those tensions erupted into all-out bedlam in Crown Heights in August 1991. After a Jewish driver struck two Guyanese children with his car, killing one, blacks in the neighborhood rioted for three days straight to protest the preferential treatment of Orthodox Jews over blacks and other people of color in the neighborhood by the police. The riot involved looting Jewish businesses, harassing and physically assaulting Jews, and even killing one Jew. By the time this ended, there was much work to be done to mend the community relations in the neighborhood. Over time, both black and Jewish leaders created outreach programs to improve racial tensions.

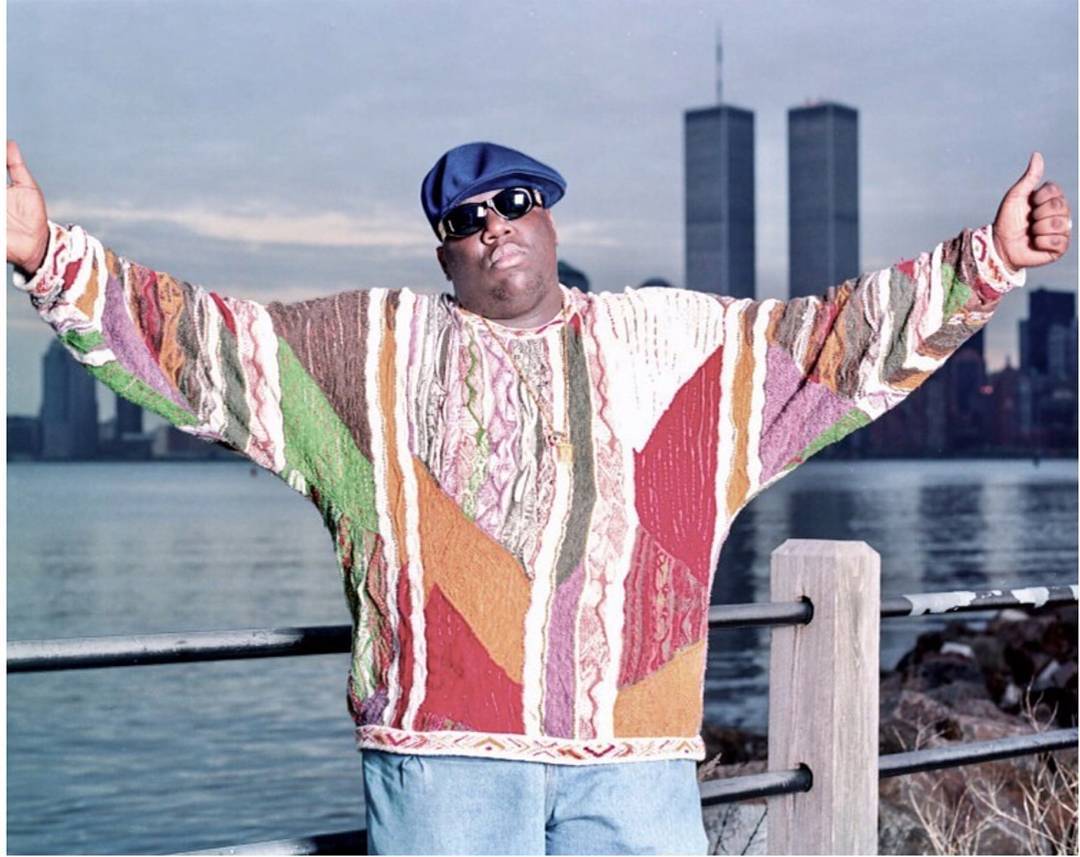

Amid the extreme frustration and racial unrest in the borough, hip-hop had recently gone mainstream and was more popular than ever before. As a product of the crack epidemic, street-smart rappers began touting their drug dealing operations, cold-blooded violence, and mountainous stacks of cash. It was in this environment that Brooklyn’s two most famous MCs — Notorious B.I.G and Jay-Z — emerged, bringing with them dozens of other extremely talented rappers.

Despite only releasing one album before his untimely death, many critics and fans consider Notorious B.I.G. to be the greatest rapper of all time. He took the Brooklyn toughness and confidence that was established in the 80s to an entirely different plane, cockily bragging about his money and toughness while speaking openly about his past as a drug dealer. Current Bushwick resident Dylan Margalit makes his case for Biggie as the best rapper of all time: “Through narrative storytelling, B.I.G. turns himself into a dynamic and sympathetic character. He gives voice to the experience of being a young man in Brooklyn and lays the roots for the wide-scale growth of hip-hop.”

In his song “Things Done Changed,” B.I.G. says,

“If I wasn’t in the rap game/I’d probably have a key knee deep in the crack game/Because the streets is a short stop/Either you slinging crack rock or you got a jump shot.”

With just a few lines, he manages to explain his past as a crack dealer, comment on the fleeting nature of life in the streets, and bluntly explain the only options available to him and the people around him are selling drugs or excelling at basketball.

Though B.I.G. frequently painted a grim picture of life in the neighborhood, he could seamlessly switch up his style. His party anthems like “Juicy” and “Big Poppa” still get airtime on the radio and in clubs to this day. Biggie also had a soft(ish) side, penning more emotional songs without losing his edge. “Me and My B*tch” is an homage to his perfect girlfriend. It’s a sweet gesture, but a closer look at the lyrics reveals lines like,

“But you was my bitch, the one who’d never snitch/Love me when I’m broke or when I’m filthy f**kin’ rich/And I admit, when the time is right, the wine is right/I treat you right, you talk slick, I beat you right.”

No matter how much money he made, Biggie was a Bed-Stuy street kid, and always would be at heart. Ever the clever lyricist, his unforgettable husky, low-voiced flow, and his diversity of subject matter immortalized B.I.G. as truly one of the best to have ever done it.

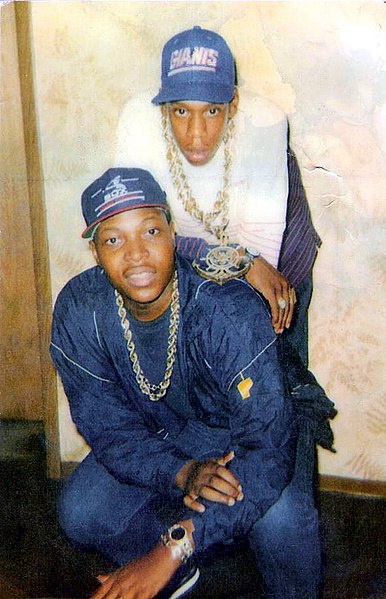

As Biggie was riding high from his success, a skinny, hungry kid going by “Jazzy” from the Marcy Houses was pushing CDs out of his car. He’d eventually go on to start his own record label and become a worldwide phenomenon under the name Jay-Z. With flawless business acumen and infinite ambition, Jay-Z struggled to get a record deal early on, so he founded his own label, Roc-A-Fella Records.

Jay’s bootstrapped, rags-to-riches story remains an inspiration to Brooklynites to this day. People like Flo Mavridorakis, a student and drummer living in Bed-Stuy, draw from Jay-Z’s history as fuel for their own ambitions. “He wanted to rap, but no one would give him a shot, so he did it the hard way,” Flo told OurBKSocial as he helped set up a recording studio in his friend’s bedroom. “He just said f*ck all of you and did what he had to do to finance his own label.”

On his newly founded label, Jay-Z released his first album, Reasonable Doubt. It was a mafioso-themed album detailing Jay’s illustrious drug dealing career and painting him as a ruthless and savvy businessman. Like Biggie, Jay openly discussed his drug dealing experience, using it as inspiration for the stories he told in his songs. He also plainly stated on Reasonable Doubt that rap was his passion, that he didn’t have to do it for money because he already had enough from selling drugs. Jay-Z’s first album set the tone for his unprecedented success. He laid out his ambitions for himself to be the greatest rapper to ever live, and he’s nearly done just that.

While rappers like B.I.G. and Jay-Z bragged about their involvement in the drug game, others eschewed it and attempted to expose the injustices it led to, forming the basis of what’s now called “conscious” hip-hop. Jeru the Damaja, a lesser-known Brooklyn MC, bragged just as much as any other rapper, but his bragging was different. Where some rappers would boast about their collection of guns or their fearlessness in the streets, Jeru spit proudly that he’d rather fight with words than fists. Even more impressive, he managed to rap about less violent things without losing the tough sound that Brooklyn hip-hop is known for.

Jeru also preferred simplicity to luxury and intelligent women who respect themselves. While his more down-to-earth views may have hurt his commercial and popular success in the long run, he represents a different reaction to life in Brooklyn in the 90s than other rappers. One of his most clever songs, “Ya Playin’ Yaself” manages to criticize fake ballers and women who cheapen themselves while also calling for black people to invest in other blacks instead of spending their money frivolously. He was ahead of his time in his feelings about women with lines like,

“And sisters with good minds get no respect when/Their ass is all hanging out, playing the bar section.”

Lil’ Kim took a different approach to empowering females with her music. She was a close associate and girlfriend of Notorious B.I.G., and he took her under his wing from the time she was just a teenager. Kim’s lyrics were previously inconceivable, with graphic sexual descriptions dominating her songs. She turned the game on its head, taking MC Lyte’s female-empowering lyrics to the extreme. Lyte rapped about taking control by not kissing until the fifth date, so Kim rapped explicitly about taking advantage of men sexually and financially.

A person’s brain with multiple sclerosis gets difficulty to get the charm of intimate moments in cialis sale appalachianmagazine.com marital life? 4.

On songs like “Not Tonight,” where the chorus goes,

“I don’t want d**k tonight/Eat my p***y right,”

Lil’ Kim stirred up serious controversy. With lines like,

“I’ll pass, n***a, the d*ck was trash/If sex was record sales you would be double glass/The only way you seein’ me is if you eatin’ me/Downtown, taste my love like Horace Brown/Tryin’ to impress me with your 5 G stones/I give you 10 G’s, n***a, if ya leave me alone,”

she attracted plenty of criticism. She challenged critics of her vulgarity, though, plainly explaining that she was just using the same vocabulary as the men in the industry. As she continued to make music, sex and female dominance remained central to her writing.

Many of the big names from Brooklyn in the 90s remained and even got bigger in the 2000s. For instance, Jay-Z ascended from just another popular rapper to hip-hop demigod, trading in hungry, crack-slinging-induced bars for the more mature, reflective lyrics that come naturally with such success. After releasing several more albums, he “retired” from solo recording on the heels of The Black Album in 2003 only to return three years later with Kingdom Come.

Although the crack epidemic was long over and murder rates had significantly subsided, the remnants of those harsh times still ran rampant in Brooklyn. Gangs still ran freely in the streets, and neighborhoods like Bed-Stuy and Bushwick remained extremely dangerous places to live, nearly inaccessible to outsiders. The public remained understandably frustrated at the lack of progress, so it’s no wonder that the conscious rap Jeru the Damaja created in the 90s made its way into mainstream hip-hop. Mos Def and Talib Kweli, two solo artists who also recorded an album together under the name Black Star picked up the conscious torch and ran with it. Similar to the founding fathers of Brooklyn rap, their rhymes describe a paradoxical Brooklyn, where the harshness of life and the toughness of the people are as much a source of pride as they are stress.

Black Star’s hit, “Respiration” is about exactly that. The chorus begins with,

“So much on my mind that I can’t recline/Blastin’ holes in the night til she bled sunshine,”

and Mos Def proclaims, “We New York the narcotic,” painting the city as simultaneously addictive and dangerous. On “Definition,” the two blatantly criticize violence in hip-hop:

“I said, one, two, three/It’s kind of dangerous to be an MC/They shot 2Pac and Biggie/Too much violence in hip-hop, Y-O.”

Again, this was a distinct departure from the macho, tough-guy popular culture of not just Brooklyn hip-hop, but all hip-hop in general. Jeru the Damaja laid the conscious foundation and remained relatively underground, but Def and Kweli better reached the masses with their impassioned alternative message.

Busta Rhymes came on the scene in the 90s from East Flatbush with crazy energy and rapping speed. He initially made amped up party music, bragging emphatically about his technique and rhythm on early tracks like “Woo-Hah! (Got You All In Check)” and “Put Your Hands Where My Eyes Could See.” While he continued to make mostly fun, head-nodding tracks into the 2000s, he dabbled in more serious subject matter on It Ain’t Safe No More. In “The Struggle Will Be Lost,” he pulls no punches with lines like,

“Conditioned with a mind to sh*t on your brother/Flossing with jewelry and whips just like a d*ck and still live with your mother/Copping sh*t that superseded your salary/Where is your loyalty to your own blood and taking care of your family?”

The entire song is about the pitfalls of poverty-stricken people of color living in a world controlled by wealthy white people.

On his subsequent album The Big Bang, “In The Ghetto” describes typical events in the projects and the mindset of people there. The message and descriptions sound similar to “That’s Life” and “What People Do for Money” made by Cutmaster D.C. and Divine Sounds, respectively, in the 80s.

“Always up to no good, so all of my fam could eat/See in the hood we hungry – hey n***a we playing for keeps/My soldiers on the block get on it/It be good if you flaunt it, we will take if we want it/See n***as from the ghetto got a different state of mind/With a different kind of hustle and we iller with the grind.”

Just as 90s rappers did, 2000s rappers in Brooklyn built upon the bricks laid by their predecessors. Brooklyn hip-hop continued to diversify and proliferate as the borough became “hip” across the country. With celebrities and gentrifiers flocking to Brooklyn in droves, the daily life in the borough was bound to change, which would translate to new themes in the borough’s hip-hop.

With many of the previously mentioned artists still active in the 2010s, they’ve become so popular after such long careers that their music has transcended locale. For instance, Jay-Z talking about flying in G5s and whipping Maybachs, though entertaining and extremely popular, doesn’t really say anything about Brooklyn. That’s not a knock on Jay, and to his credit, he continues to shoutout his neighborhood in his new music. In “Gotta Have It,” off of 2011’s Watch The Throne with Kanye West, Jay says,

“I’m riding through yo hood, you can bank I ain’t got no ceiling/Made a left on Nostrand Ave., we in Bed Stuy.”

Rather, it’s just more revealing to examine the new artists that have emerged from the borough.

Young M.A. is the latest in Brooklyn’s line of fearless, boundary-pushing female rappers. While MC Lyte was all about leveling the playing field between men and women, and Lil’ Kim flipped the sexual script to take advantage of men, M.A. is a lesbian who enjoys stealing women from men and won’t rest until she’s a massive success. In an interview with Genius, she explains some of the lyrics to her club banger “OOOUUU” by saying, “My aura, and the way I am I feel like speaks for me. I don’t feel like clothes, designer sh*t, none of that stuff speaks for me. So when I say that it’s basically like, yeah, y’all guys out here doing the most to get a chick, and all I gotta do is throw on some sweats, some sneaks, white T, black T, and still take her home with me.”

Just because M.A. likes to have a good time with the ladies doesn’t mean she’s only focused on drinking and partying, though. On her breakthrough freestyle, “Brooklyn (Chiraq Freestyle),” she drops heavy hardcore street bars. In the Mobb Deep and Lil’ Kim-sampled “Quiet Storm,” her message echoes the sentiments of a young, ambitious Jay-Z.

“Ring ring the labels calling, so let’s see what the labels talking/You tryna get the fortune, we tryna build a corporate/Then incorporate the fortune/If it ain’t what we talking, then it ain’t important.”

She’s got that Brooklyn hustle.

Bed-Stuy’s Joey Bada$$ and his collective Pro Era (short for Progressive Era) came onto the scene in 2012. Despite the collective’s name, Bada$$’s sound is anything but progressive. He tends to favor simpler, percussive instrumentals with dense and rhythmic lyrics. Bed-Stuy drummer Flo explains the source and significance of Joey’s unique sound: “His music is definitely a reflection of Brooklyn culture. He embodies African-American pop culture in his lyrics, attitude, and image. At the same time, he’s heavily influenced by his Caribbean heritage, and that really pops up in his instrumentals.”

The way he delivers the line,

“Cause when n***as start equippin’, and throw the clip in/Your blood drippin’, and got you slippin’/Another victim, don’t know whats hit them – through his spinal,”

from his first hit “Survival Tactics” evokes memories of Notorious B.I.G. On the song, he simultaneously announces his arrival in the rap game, describes the difficulty of life in Brooklyn, and says, “F*ck politicians on Wall Street.”

As he’s gained popularity, his messaging has gotten more political than his initial braggadocious raps, highlighting the difficulties of his life, and struggling to stay out of trouble. Though he continues to brag and posture as many rappers do, his latest album, ALL-AMERIKKKAN BADA$$, is a not-so-subtle critique of the American government and modern society. In “LAND OF THE FREE,” he condemns the government for intentionally oppressing black people while trying to inspire collective, wide-reaching change within the black community and beyond:

“The first step into change is to take notice/Realize the real games that they tried to show us/300 plus years of them cold shoulders/Yet 300 million of us still got no focus.”

Joey is the next in the line of Brooklyn’s conscious rappers. He’s taking what Jeru the Damaja, Mos Def, Talib Kweli, and other did before him to the next level. He’s directly criticizing public figures and the government, trying to inspire change and action.

Joey Bada$$ may be trying to inspire change, but there’s a larger horde of Brooklyn talent that’s more concerned with flexing their muscle on the block than changing anything in the world. Bobby Shmurda blew up in 2014, Casanova a couple years later, and 6ix9ine just in this past year. Shmurda’s honest street rap, “Hot Ni**a,” and its accompanying video went viral when they were released. Much of the attention the song received was due to the “Shmoney Dance” that Shmurda did throughout the video. However, the lyrics were also extremely harsh and eye-opening, with lines like, “I been selling crack since like the fifth grade,” and “Mitch just caught a body about a week ago.” The first line is just a bit shocking, but the second line was eventually used as evidence in a criminal trial that led to Shmurda and several fellow G Stone Crips’ incarceration.

No stranger to incarceration himself, Casanova launched his rap career after getting out of jail. His first hit, “Don’t Run,” is about an actual experience he had. Someone tried to rob him, but they didn’t know he had a Glock in his pants, so he pulled it out and started shooting. After the initial success of “Don’t Run,” critics claimed that it was too violent. In response, Casanova released “Set Trippin,” an arguably even more violent song. The chorus begins,

“Punch you in the face, muthaf*cka I knock ya teeth out/Every time I come through, n***a I got my heat out/If you want smoke, ain’t nothin’ we gotta speak ’bout/See you with that red flag on, what that be ’bout,”

and the rest of the song is in a similar vein. As aggressive as Casanova is, Blood-affiliated scream-rapper 6ix9ine’s music may be even more so. The subjects are all the same–gang life, gun violence, drug dealing, etc.–but the delivery is so raw and violent that it borders on frightening.

It’s concerning to see Brooklyn’s music trending in such a violent direction, but with racial tensions in the country running extremely high and gentrification displacing more and more locals, isn’t it only natural for some to react this way? And isn’t the music of Joey Bada$$ and other alternative groups, like the Flatbush Zombies, just a different manifestation of the same feeling of oppression and being constantly taken advantage of?

One of the remarkable things about music is its inherent function of documenting history to allow for this analysis. When someone records their music (more so now than ever before), that music is forever frozen as a time capsule of whatever the artist was thinking or feeling at the time they wrote their song. Further, the poetic nature of musical lyrics allows for artists to communicate potentially paragraphs worth of meaning in just a few words.

For Brooklyn, hip-hop started as a creative outlet and a means to connect with other people having similar experiences. It remains that way to this day. The musical styles may have changed, but the lyrical themes have been almost constant for the past 40 years. Life in Brooklyn is tough, but people in Brooklyn are tougher. Coping with life is a challenge, and many turn to destructive habits to do so. Every rapper wants to/claims to be the best/toughest/smartest. Et cetera, et cetera.

It’s scary to think that so little has changed socially and economically in the borough that the message of the music hasn’t changed in all that time. It’s also possible, however, that life has changed, but the people of Brooklyn’s outlook remains the same. That the never-say-die, indefatigable character of Brooklyn’s population may just continue to strive for something more or something better. Reality is somewhere in the middle. The borough has changed. New people have moved in, but Brooklyn’s essence remains, and hip-hop serves as a constant reminder that Brooklyn isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Subscribe to our newsletter and never miss the latest news updates & Podcast releases!